Inside Oklahoma Contemporary’s most high-tech show yet

Art isn’t made in a vacuum — it’s not installed in one, either. That’s certainly the case for Bright Golden Haze, the inaugural exhibition opening at Oklahoma Contemporary’s new home at NW 11th and Broadway on March 13. This illuminating group show explores light and place through a variety of contemporary works, including sophisticated 3-D installations that require an all-hands-on-deck approach to making the kind of magic that sparks imagination and stops you in your tracks.

Steve Boyd, exhibits manager at Oklahoma Contemporary, is one of those magic makers. Boyd oversees exhibition planning and implementation of gallery works, along with managing our robust public art program at Campbell Art Park. Alongside Curatorial and Exhibitions Director Jennifer Scanlan, who oversees all exhibition programming, the two have a combined 40 years’ experience in crafting and executing show-stopping exhibitions with lots of moving parts.

Focusing on a few of the more technically complex works from our opening show, Boyd and Scanlan sat down to talk about the behind-the-scenes labor and collaboration, along with safety and aesthetic considerations, that go into creating a world-class arts experience like Bright Golden Haze.

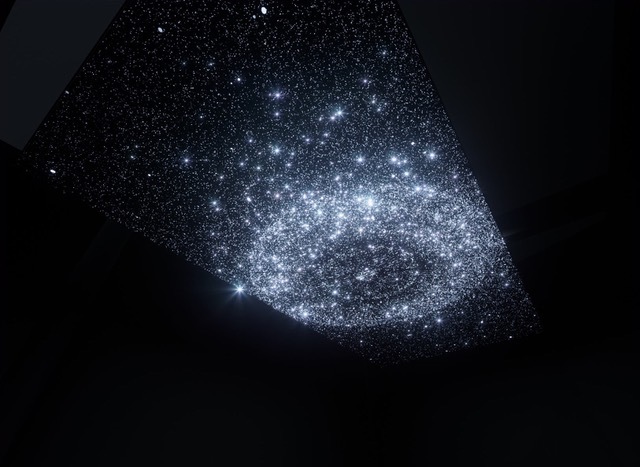

Star Ceiling 2 by Leo Villareal

How, exactly, does one hang the stars? Boyd has been asking himself that question as he gears up to oversee a team installation of Leo Villareal’s Star Ceiling 2. The work creates the dazzling effect of a starry night sky, suspended above the viewer in an immersive environment built to the internationally acclaimed artist’s exact specifications.

Boyd brought in a local rigging company to help ensure safety during installation. “Since we're working above our heads, we needed somebody experienced with that who knows exactly what they’re doing,” he said. “This kind of rigging is not unlike what you’ll see at a rock concert — or a musical or play, where they hang all the lights and all the scenery. It’s almost like Legos. The metal pieces just fit together and you can make anything out of them. That's what will go up in the ceiling to hold the installation.”

Crafting the cosmic wonder of Star Ceiling 2 also required close collaboration with the artist and his team. “We brought out people from his studio, because it's a technology the artist has developed himself,” Scanlan said. “So for that case, the technology is proprietary information we don't know anything about. It's his artwork, and what Steve has needed to do is develop the rigging system and work with those elements in the right way.”

Villareal’s studio team had other specifications in mind, from the color of the paint on the walls to the carpeting on the floor, to the benches where visitors will sit and look up in awe “The artist is very specific about how he wants this installation to be, down to those kinds of details, so people will have the kind of experience he wants them to have,” Scanlan said.

Ḱanḱagawí (The Seam of Heaven) by Marianne Nicolson (Dzawada'enuxw First Nation)

Like Star Ceiling 2, Marianne Nicolson’s Ḱanḱagawí (The Seam of Heaven) keeps an eye on the cosmos. The breathtaking sculptural installation compares the imagery of the Milky Way to the Columbia River, drawing from the cosmology of the artist’s First Nations heritage. Also like Villareal’s work, the installation process requires thoughtful consideration and an expert hand.

For Scanlan and Boyd, it also required some customization. The work was originally installed at the Seattle Art Museum with each of its glass panels arranged back to back — but the new gallery space at Oklahoma Contemporary required a different approach. “We wanted to really emphasize the shadows on the walls, and we don't have the kind of great big open space that worked well in Seattle,” Scanlan said. “So we set it up in its own room with a slightly different installation that works better for us.”

Oklahoma Contemporary called in LA-based exhibition designers Chu + Gooding for help laying out the exhibit and consulting. “We knew this was going to be really technically difficult show, and we were going to be dealing with a lot of things involving lit spaces or dark spaces,” Scanlan said. “We worked with them to really come up with something that not only worked for the visitor, but also incorporated all of this technology.”

Untitled (1NSA) by James Turrell

Transmission light work, 2007

61 ½ x 39 ½ in.

The instructions for installing James Turrell’s Untitled (1NSA) light sculpture call for “several strong people” to lift its centerpiece 250-pound hologram. Luckily Boyd has some help. His weekly in-house crew will fluctuate between four and six workers, not including members of artists’ out-of-town teams onsite to make sure works like these are presented to the public as the creators intended.

For Turrell’s space-generating light work, this meant even more careful-than-usual attention to detail. Turrell's work is a hologram, a kind of two-dimensional image which can appear three-dimensional when light hits it in a certain way. “But that light has to be in exactly the right spot. It has to hit at just the right angle and be just the right distance back from it,” Boyd said. “We’ll fabricate a sort of holder for the light, and we’ll probably be up on the lift for quite a while, with people on the ground, just trying to find that sweet spot.”

Boyd, Scanlan and the rest of those involved behind the scenes in Oklahoma Contemporary exhibitions will be searching for that sweet spot over and over again, work after work. The unique considerations made for Turrell’s Untitled (1NSA) may not be the same as those for Villareal’s Star Ceiling 2 or Nicholson’s Ḱanḱagawí (The Seam of Heaven), but each piece that comes through the newly built bay doors will require the same careful consideration led by teams of experts.

If all goes according to plan, when you walk in to experience Bright Golden Haze for the first time, you’ll never know they were there.

Return to New Light.