The Art of Food: How many big names can one exhibition hold?

A common theme among contemporary artists is to not imbue their works with their own perceptions, ideas or agendas, in hope that viewers form their own narratives. But do certain “big” names carry their own connotations? If we dive deeper into these artists, will our relationships with their work change?

When it comes to big names and heavy hitters, The Art of Food: From the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation pulls no punches. From Warhol and Rauschenberg to Holzer and Hirst, influential and well-known contemporary artists anchor this exhibition. And yet, for some, these names are simply words on a label.

How do we form connections to works if we don’t know the artists? Do their names hold more power than their pieces?

Lorna Simpson’s works, for example, encourage this relationships with viewers. Simpson became prominent in the 1980s with a conceptual approach to photography, joining a generation of artists who utilized conceptualism through language and images. Simpson creates a diptych of reality in her The Art of Food piece, C-Ration. The anonymity of the body speaks to degradation and dehumanization experienced by enslaved Black women who were forced to serve in the households of their oppressors. Simpson’s work challenges ideas of representation, identity and gender, evoking feelings that many marginalized and other-ed groups experience daily.

Hung Liu, like Simpson, pokes at the nature of representation. Her Art of Food work highlights the propaganda and warped views around women laborers in China, overlaying historical photographs to blend the past and present. In these depictions, viewers can find stories of those typically left out of the narrative.

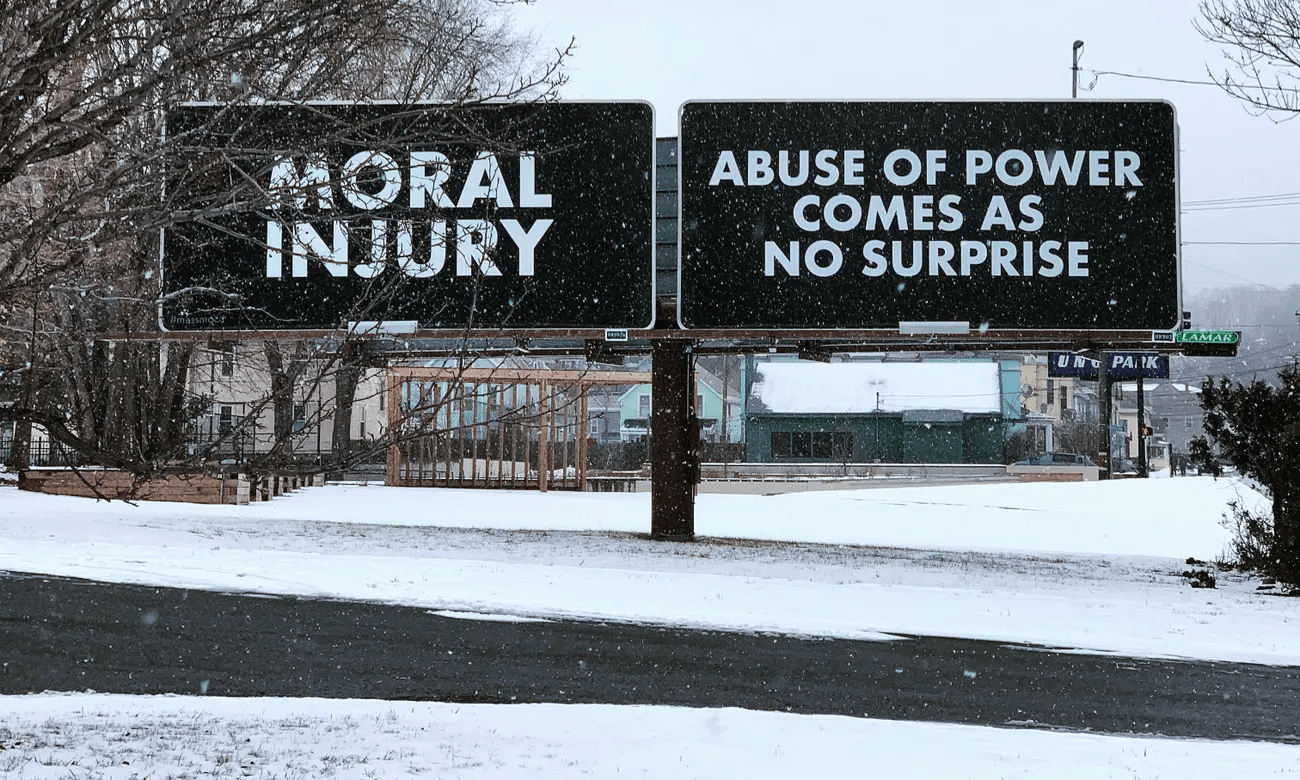

Liu and Simpson are not alone in offering a means of connection. Jenny Holzer is best known for her use of words and text in her conceptual installations, producing works meant for mass consumption. From T-shirts and billboards to LED signs and condoms, Holzer’s words have appeared on many surfaces. In The Art of Food, the artist’s work focuses on a skewed concept of food justice, where food is a privilege, not a right. With text as the central focus, Holzer directly confronts the world and those who hinder it and its people.

But what happens when words and food (literally) meet? Like Holzer, Ed Ruscha evokes mixed feelings and ideologies through text. The Oklahoma-raised artist is known, and self-described, as someone who “paint[s] words like someone else paints flowers.” A typography king, Ruscha uses text as a means of communication, similar to Holzer and Simspon. Ruscha’s News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews & Dues Series is a duet of language and food, the piece simultaneously commenting on British culture while rendering food inedible — pie filling, baked beans, chocolate syrup and more are the mediums on display.

This inedible duality is also paralleled within Damien Hirst’s works. While Ruscha’s food use overlapped with social critique, Hirst meets food and pharmaceuticals at a consumerism convergence. Hirst, never one to shy away from grabbing the viewer’s attention, is known for his provocative animal corpse pieces. In The Last Supper, Hirst centers the realities of food production and pharmaceutical use. Interestingly, the artist is now part of the British culinary scene, responsible for a number of newly designed restaurants.

While Hirst and Ruscha utilized organic materials, Robert Rauschenberg was known for his coining of the term “combines,” by where, you guessed it, he combined multiple mediums into a single work. These radical-at-the-time methods led to his position as one of the influential American artists of the late-20th century. This combination technique is on full display in The Art of Food — Hirst’s L.A. Uncovered Series a transformation of photographs depicting the city’s urban textures, the print a collage-like interpretation.

Another big name, Andy Warhol ushered in the ‘60s Pop Art movement, blurring lines of mainstream aesthetics and fine art. A similar argument can be made about ceramicist David Gilhooly. While the two worked in vastly different mediums — Warhol with prints, paints and installations and Gilhooly with clay — their commitment to the Pop Art vibe is apparent, as is their cheeky commentary. When asked to simply “paint some cows,” Warhol did just that, plastering “Betty the cow” on repeat. In order to encapsulate the American fast food spirit, Warhol created a number of hamburger artworks, the icon of American culture repeating throughout his career. Also on view in The Art of Food, two rarely seen Warhol watercolor, worls away from Pop Art. Though lively, the bar scenes conjure feelings of loneliness.

Gilhooly’s Lite/Late Lunch evokes the super-sized Americanism Warhol speaks to, juxtaposing eating disorders. The artist said “only after dealing with the subject of food for many years did I realize that Food itself was becoming sentient, lurking in the background, waiting for us to overstep.”

While these big names — Simpson, Liu, Holzer, Ruscha, Hirst, Rauschenberg, Warhol and Gilhooly — hold prominence and influence, viewers flock to the works, not the artists themselves. The works draw us in and create how we identity with them and the stories they tell. So: What is in a name?

As the exhibition opens, we’ll continue to hold conversations and pose questions around the artists, their names and their artworks. Opening celebrations for The Art of Food kick off at 6 p.m. Feb. 9. We invite our 21-and-up audience to be among the first to view this vast collection, along with hors d’oeuvres, drinks and a live DJ. Reserve your tickets today. (Members get in free.)

The Art of Food was organized by the University of Arizona Museum of Art in partnership with the the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. It was curated by Olivia Miller, interim director and curator of collections at the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Images:

Installation view of Damien Hirst's The Last Supper (1999) in The Art of Food. Photo: Deann Orr / Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation.

Installation view of (left) Jorna Simpson's C-Ration (1991) and (middle) Jenny Holzer's Survival Series: If You're Considered Useless No One Will Feed You Anymore (1983-1984) in The Art of Food. Photos courtesy the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Jenny Holzer's Abuse of Power Comes As No Surprise and Moral Injury (2020). Photo courtesy The Guardian.

Installation view of (right) Ed Ruscha's News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews & Dues Series (1970) in The Art of Food. Photo: Deann Orr / Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation.

Installation view of (left) Robert Rauschenberg's L.A. Uncovered Series: L.A. Uncovered #3 (1998) in The Art of Food. Photo: Deann Orr / Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation.

Installation view of (left) Andy Warhol's Banana (1966). Photo: Deann Orr / Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation.

Return to New Light.