Crafting the perfect environment for an epic Odyssey livestream — from 2,000 miles away

By Carl Faber, lighting designer

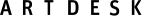

This month, I had the pleasure of designing the lighting in the Te Ata Theater for Oklahoma Contemporary's marathon livestream reading of The Odyssey — and I did it entirely remotely from my home studio in Portland, Ore.

Typically, a theatrical lighting designer is onsite at the venue for days or weeks leading up to a performance, putting in 14-hour days in close quarters with the rest of the team. It’s not uncommon for a designer to fly in from out of town to complete the bulk of their work. None of that is feasible in a global pandemic, so we reimagined the entire in-person experience, supported by a complex network of remote systems and platforms, to make it possible for me to do my job from my desk across the country. This is how we did it.

I should preface this by acknowledging my privilege. I have a home studio, with equipment I’ve collected over years to accommodate a way of working I’m fortunate enough to pursue. I am a white man who has been afforded many opportunities in my career and education, and those opportunities created the conditions for me to enjoy the privilege of trust in a process that was, in a very real sense, an experiment.

There was always the risk that the technologies and intercommunicating systems might fail, and while we were fortunate that everything functioned as we’d hoped, this was made possible by a diligent, resourceful production team operating in a newly constructed theater. For that, I am humbled and grateful.

If you’re curious what a theatrical lighting designer actually does, there are lots

of books

and articles

that do a much better job than I ever could at explaining what we do and how we do it. Every project is different, but in broad strokes, there are usually several phases of a lighting designer’s process, and almost every one typically requires an in-person presence. Our challenge: as best we could, replicate the experience of having a designer in the room, via remote platforms. Below, I’ll compare a pre-COVID process to ours.

Our challenge: as best we could, replicate the experience of having a designer in the room, via remote platforms.

Phase 1: Concept Development and Design Meetings

At the start of a typical process, the creative team will usually assemble in a physical space and share ideas and thoughts for what they intend to achieve, often showing visual research or inspiration. For this project, those meetings happened, unsurprisingly, over Zoom. I usually bring art and photography books filled with Post-it Flags, images and clippings — tactile objects to pass around and compare against each other. This time, I prepared a presentation deck on Keynote, screen-shared it during the Zoom meeting and distributed it as a PDF to the team via Dropbox. Typically, a scenic designer will construct a physical, to-scale architectural model of the design for us to touch and manipulate with our hands. For The Odyssey, I leaned heavily into 3-D renderings.

I draw a stark contrast between physical/analog/hand-held and virtual/digital/screen-based collaboration to emphasize that while the transition to digital in collaborative spheres has been happening for a while, it’s certainly found its moment now, when we’re discouraged from gathering and touching. Because I knew I wouldn’t be able to see the theater in person, a photorealistic 3-D representation was the clearest way to visualize the space, develop lighting ideas and communicate them to the team. I recommended some framing and video shots that would work well with the design and presented some “looks” or stage pictures that I felt would be compelling. Almost all of these ideas carried through into the final design seen by the livestream audience.

Most of us who work in this business used some form of remote digital collaboration pre-COVID, but this initial phase is often in-person, and it’s one of my favorite parts of the process. It’s my belief that a multi-sensory experience of any object — holding it in your hands, hearing how it moves, breathing it in — commits it to a different and deeper part of our brain. That will never be possible over Zoom. Reading the full body language of a collaborator and aligning your attention fully to their thoughts and presence is something we’re losing in physically distant interaction, and there’s no doubt that it’s detrimental to a remote design process. I have no work-around suggestions or brilliant ideas for mitigating that, except to say that in this instance, in my physical absence, a PDF of 3-D renderings was pretty useful.

Phase 2: Technical Drawings and Pre-Visualization

I’m used to doing this part solo, so the drawing part of this phase was probably as close to the normal way of working as we got. I did what I usually do: went into my studio with equipment lists, groundplans and a list of design ideas and created a light plot for the stage crew to use as a blueprint for installing the stage lighting. Concurrent to this, I was also preparing a showfile, based on my template file, to load into the theater’s lighting console, containing preliminary lighting levels and timings for each sequence. Prebuilding scenes and stage looks “offline” (or, away from the lighting console) is common practice, but most offline editors have traditionally been limited to showing mostly numbers and text, with no visual or 3-D representation.

In the past this programming was, at best, educated guesswork. By linking several applications, designers wanting a virtual 3-D environment could pre-visualize

a design, but the time, expense and complication involved often outweighed the benefits for small to mid-size projects. As a result, many designers, myself included, hardly ever did it. But that all changed for this project, because the technology to integrate industry-standard lighting control and a 3-D programming environment into a single piece of software, EOS v3.0 with Augment3d (available for free), was literally in the process of being built, and we used it.

In fairness to the developers, I won’t dig into the details of how we applied unreleased software to our production, but rather emphasize that the digital landscape is changing daily, and I saw that firsthand on this project. I would be working though my design, install a new beta release, and instantly, new features were possible. The speed of innovation, even amidst a pandemic, is hard to overstate. This software's release will be a major breakthrough in lighting technology. It’s coming at a moment in time when, globally, we can use it in ways we never could have imagined pre-COVID.

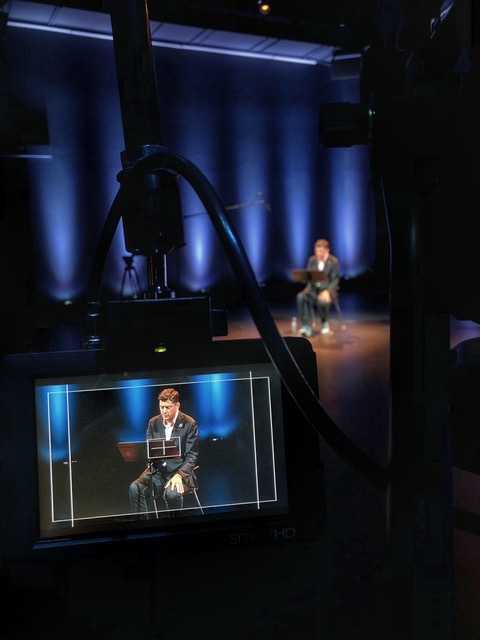

As I drafted my plot, I’d confirm in the virtual environment that my shots would work and we’d be able to achieve the design I’d conceived. By the time the plot was finished, I’d created a fully programmed showfile that looked beautiful in 3-D, ready to load into the on-site lighting console, all without ever having stepped foot in the theater. Because this software wasn’t released pre-pandemic, and nearly all theater production has been COVID-canceled since March, this is likely one of only a handful of fully realized productions, to date, utilizing Augment3d.

Phase 3: Load-in/Installation and Focus

The lighting designer is often not in the theater for load-in (when the crew hangs the lights), but it’s almost unheard of for a designer (or their associate) to miss focus (when the lights are aimed). But this time, I was present for both, virtually, from my desk in Portland, via a live feed and a phone call.

Prior to load-in, to allow the crew to get the lights roughly pointed in the correct position without me, I took rendering captures from Augment3d, and prepared what I called “Pre-Focus Charts” using Moving Light Assistant, a touring-industry-standard application that’s usually used after a show has opened to archive how lights and looks appeared onstage. A key part of the novel approach we applied throughout was to use applications in ways different than they were originally intended to be used.

At focus, we established a screen-share link between my studio laptop and a laptop directly networked to the on-site lighting console, so I could, from Portland, turn on lights and run cues in Oklahoma. In the week prior, I had tested several different remote screen-share setups with a colleague in New York to determine the most functional workflow for our situation. With a digital landscape flooded with feature-rich possibilities, the question isn’t if we can do it, but which, of the many applications, serve us best.

While screen sharing isn’t particularly new, using it in a theatrical setting to allow a designer to control lights from across the country was seldom considered pre-COVID, when it was far easier to facilitate safely bringing the designer to the site. In this moment, faced with a new set of conditions, long-distance remote lighting control reduces COVID risk both to the designer and everyone else on-site, thereby making it suddenly a lot more desirable.

With one live feed, a bird's-eye camera from above and a second camera on the stage level, I could see pretty much everything, and was able to talk through the exact focus specifics of each light with the onsite crew. You’ve probably heard of “phoning it in” — that’s literally what I did.

The question isn’t if we can do it, but which, of the many applications, serve us best.

Phase 4: Technical Rehearsals and Cueing

This is a phase when you usually really need a lighting designer in the room. Adjusting levels, timings and sequences — there’s lots of real-time, creative problem solving involved, and communication with other departments is essential. Same as Phase 3, I did this all from my desk, looking at monitors, controlling the lighting remotely, with a voice link to communicate with everyone in the control room in Oklahoma.

Was it perfect? Of course not. But with a direct live feed of exactly what the livestream audience would see, I was for all intents and purposes seeing a true-to-TV representation of my design. It mattered less what it looked like in person than what it looked like on screen, and I had a perfect view of that. Artistic Director Jeremiah Matthew Davis and I talked through each look and sequence, comparing to my design decks and making live adjustments based on what we saw.

I was fortunate to have known and worked with Jeremiah for years prior to this project, and the value of that collaborative history, in this phase in particular, was key. We have a shared vocabulary that allowed us to move quickly and efficiently despite communicating remotely. And while I had never worked in the Te Ata Theater before, I had worked with all of the specific models of LED lights we used, and drawing on that past experience was valuable in shaping the design remotely. I brought in color palettes that I’d built and used before, and I trusted that those tools would look and behave like they had for me previously. When designing remotely, there is no substitute for that trust in your tools.

During my earlier pre-programming sessions, I had set up the console’s cues and submasters to be easily operated by one onsite lighting technician, Nolan Baker, who could walk around the whole theater troubleshooting and fine-tuning adjustments, with me in his ear, talking over the phone via his AirPods — a cross-continental intercom, essentially.

Maybe the biggest miracle of all: We got all of this to work, with essentially no delays, via my studio’s DSL internet. Nobody’s more shocked than me.

Phase 5: Performance

I watched the livestream on the same online platforms as the rest of the audience. An hour before the stream began, I shut down all of my remote programs and put the show entirely in the board operator’s hands. Everything ran as smoothly as we’d hoped and planned. A lighting designer typically “walks away” after opening and allows the show’s run crew to take it from there, and that’s what I did … about 20 steps, to my backyard.

There exists opportunity to make art with light remotely, and technology has, to some extent, democratized that access.

Conclusions

One might ask: So, we don’t need lighting designers in the theater anymore? I for one definitely don’t think that’s true — at least, I certainly hope not. At the outset, I pitched this system of remote platforms to Oklahoma Contemporary as a proof-of-concept, asking: Is this even possible? Turns out: yes, but I would not advocate for this approach for every project.

At all times I felt both technologically connected, but emotionally disconnected, and that is not a comfortable place for an artist. The discomfort might have been “worth it” to achieve a positive result for the viewers, but, from my experience, remote design is still very much experimental, and we collectively have a long way to go to fully replicate the experience. Technically, it’s also important to remember that this particular system of remote working was feasible largely because what I was seeing on my own monitors at home was the same view the livestream audience would be seeing. Designing through an RGB screen for a live audience looking at full-spectrum light would require a much more advanced setup. This was, throughout, an experiment, and while it would be fair to call it a success, it would also be fair not to draw too many conclusions from it, without a wider sample size.

One might also ask a much more complicated question: Why not just hire a local designer? As a designer who had, prior to COVID, worked both near to where I lived, and in some cases very far away, it’s a complex question that’s often at the forefront of my thinking. There’s much that could be said here that I’ll leave for another discussion elsewhere, so that I might drill down to a central intention of this COVID-specific process: removing the designer from the physical space entirely.

Many organizations, including my union, are deeply concerned about COVID protocols when returning to work. Institutions dependent on mass gatherings are scrambling to respond to the science and create a safe work environment, but of course, the safest practice is to remove ourselves from the environment altogether, and when that isn’t possible, put as few people in the room as you can. It was my goal from the start to make everyone in the room just a little safer by removing a breathing body (me) from it. Once you remove that person from the room, the current digital landscape for connecting that person back in, via technology, makes it irrelevant if you’re across the street or across the country. The connection speeds and tools you’ll use will be, essentially, the same.

It is my genuine hope that by documenting and explaining my process, another designer under a different set of conditions or with a different set of opportunities can take this case study and run with it. Many of the applications I used (Augment3d, Screen Share, Zoom, Keynote) are free, and again, I did this on DSL internet service.

I am also conscious that the theater and live-event production industries are, like so many others, rife with systemic inequities, producing barriers to entry that free software and comparatively low-speed internet cannot, on their own, overcome. At a time when so many theater artists and technicians are out of work, I have admired those in my community who have used this “down time” to educate themselves and others.

I was excited to openly share the inner workings of this particular process precisely because I hope it might serve as a road map for others to consult. But of course, there’s privilege there too: I had a job this week. I did that job from home, using internet and computers. Many don't have that. If there’s a single takeaway from this experience, I hope it is that there exists opportunity to make art with light remotely, and technology has, to some extent, democratized that access.

Nobody, least of all me, wants this type of remote working in the theater to be the norm. The event we could have produced had I been in the room would have undoubtedly been different in some way, and it’s often painful as a theater artist making temporary work, not knowing what could have been. Watching the first evening of readings from a different time zone was bittersweet.

I confess, there is a more traditional part of me resistant to a digital future. I was, only six months ago, standing in a theater holding a clipboard with paper stapled to manila folders. But we are living in a moment of evolution and adaptation, venturing outside of the manual, modifying our lives and the systems that support them to meet the moment. Designing like this was strange, and I am desperate to get back into a physical space with my collaborators. But until that time comes, I’m adapting, listening and learning, and attempting to turn that into action. And if the digital landscape makes opportunities like this one available, I’m all in.

DISCLAIMERS:

- EOS 3.0 was publicly released the same day this article was published. I used a pre-release Open Beta version (which the developers generously made available to advanced users with the express directive that it was not fully-supported software) for pre-programming and renderings. The console at the theater was running v2.9.1.

- Never put a light board directly on public internet. My method of screen sharing, while safer than putting a light board directly on public internet, is not a manufacturer-supported feature.

- Never remotely control a light board without qualified crew on-site. I only took remote control when I had direct verbal confirmation that the crew was in the theater and ready to ensure the safety of the room and everyone in it.

Gratitude to (alphabetically): Benjamin Travis, Bobby Bermea, Geoffrey Jackson Scott, Isaac Lamb, Jeremiah Matthew Davis, Jollee Patterson, Sarah Marguier, and Tommy Noonan.

Carl Faber (he/him/his) is a lighting designer for theater, dance, opera and immersive experiences. He is a proud member of the United Scenic Artists Local USA-829, of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). He lives on the traditional territory of the Cowlitz nation otherwise known as Portland, Ore., with artist Sarah Marguier and their son.

Return to New Light.