Reflecting on the journey of John Newsom through the exhibition's catalogue

For 144 days, we have walked on the wild side. Towering cats greeted you upon entry, as charging bison headed your way. Swing left, and you wandered into a world high in the trees, bustling and chirping canopies. Hang a right, and you see the creature-filled tour had only just begun, snakes, mice and scorpions in line, one by one. John Newsom: Nature’s Course offered fantastical views of flora and fauna, sights that will be missed as it leaves our second floor gallery.

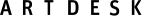

Oklahoma Contemporary Director Jeremiah Matthew Davis worked directly with the artist to plan this exhibition, hand-selecting works to include. We wish Newsom’s world a farewell with portions of Davis' essay from the exhibition’s catalogue.

By Jeremiah Matthew Davis

John Newsom does not exactly paint his paintings. He builds them, layer by layer, methodically constructing the colors, textures, and compositions. For more than 20 years, Newsom has set about building a body of work that weaves together distinct techniques, inspired by art historical movements, to forge a style uniquely his own. Combining the energy of gestural abstraction, the hard-edged geometry of minimalism, and the painterly depiction of flora and fauna, the artist creates richly textured, densely packed explorations of allegory. These are the works of a classically-trained draftsman, a master builder.

Painting for Newsom is serious, committed labor, pursued with monastic dedication. He is in the studio on a regular schedule. He arrives, changes clothes, locks his phone in a drawer, and gets to work with the focus of an athlete training for a championship. He builds his own stretchers; he stretches and prepares own his own canvases. He employs no studio assistants. While Newsom is warm, gregarious, and friendly in the world, he is ice cold, solitary, and fierce in his studio practice. Working with the intense physicality of an action painter, John has developed powerful hands — the size of catcher’s mitts — from using atypical tools for fine art (like mops and trowels) to construct his paintings, beginning by laying them flat on the floor to throw arcs of paint on the surfaces.

The foundations for Newsom’s approach to artistic production lay in the Great Plains — specifically Kansas, where he was born, and Enid, Oklahoma, where he was raised. Two core elements of Newsom’s signature style can be located directly in this place: horizontality and the natural world. Central Oklahoma is a juncture between the Great Plains and the American West, where the sky completely dominates a landscape that expands outward and horizontally for miles, uninterrupted by large bodies of water or mountains. This expansive quality can be observed in each of the artist’s works since Labor of Love

(2001); the large-scale canvases are filled, edge to edge, with compositional information, threatening to burst from the frame and extend into infinity.

Newsom’s deep connection with nature can be readily found in his work, but layer upon layer of reference and influence are also embedded in his paintings. To scratch the surface is to discover a surfeit of allusions to artists of the past, American culture, and music.

The thirty-one paintings in his mid-career retrospective, John Newsom: Nature’s Course, overtly reference nature and its cyclical patterns. Life and death often occupy the same frame: Mice forage in dangerous proximity to a snake, a hawk descends toward its prey, a wolf unleashes a blood-curdling howl. For the artist, animals represent human emotions and ideas: A charging bison stands in for ambition and a triumphant return home; a black widow wandering with its prey amidst a clutch of tulips represents both the rebirth of spring and the reminder that death is a part of life.

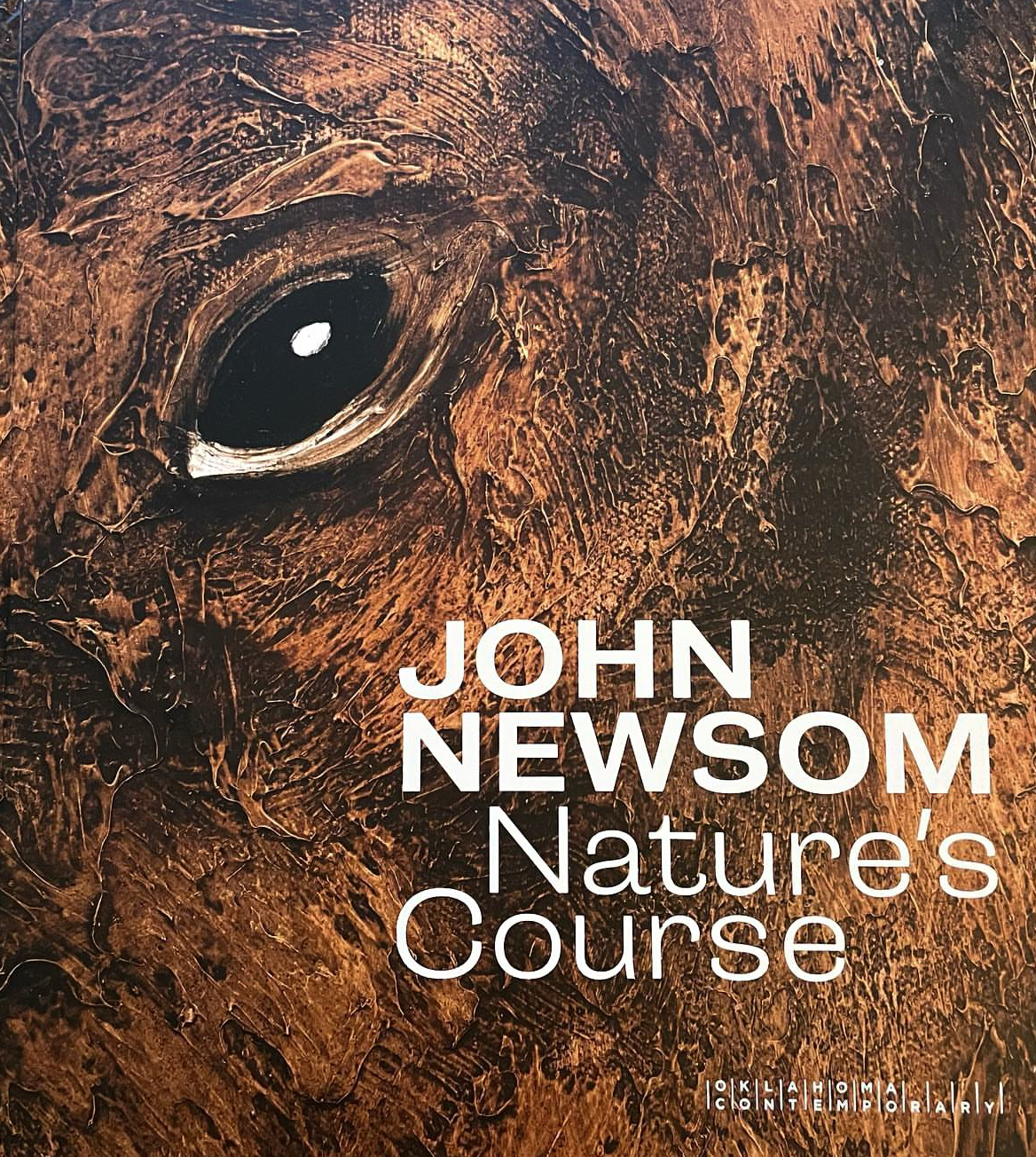

When discussing how the music of groups like the Wu-Tang Clan influenced him, Newsom reflects first on the formal experimentation that struck him as especially “colorful.” “Our generation of painters’ painters embraced [the Wu-Tang Clan’s] pluralistic approach to creation,” he says, “and also the loud keyed-up delivery.” Newsom sees music as a zone of “complete abandonment” and an immersive experience for the listener. Likewise, he wants his paintings to fully activate the viewer’s sensory perception. The respect is mutual: Newsom and his work have been known and admired in the contemporary hip-hop scene as well. The major hip-hop marketing executive and producer Gustavo Guerra says, “John is an important artist in our community.” This exchange of influence speaks the interconnectivity of the arts. Artists and their disciplines are not compartmentalized and hermetically sealed from one another. The arts — visual art, music, dance, theater, design, architecture — depend on one another. Living artists influence and inspire each other by rubbing elbows at the right time. Without the connection to music, specifically to Raekwon and the Wu-Tang Clan, Newsom would have undoubtedly charted a different course in his career.

The arc of John Newsom’s career began at a time when many were proclaiming the death of painting as a medium. New forms were in; established media were out. Newsom charged forward with his work nonetheless, building on established practices dating back centuries to create an original approach. The painter “holds his course” and maintains a distinctive style. He reads and learns, but he does not change with the tides. Arguably the most influential MC of all time — Rakim — described his creative approach in a way that resonates with Newsom’s. Rather than follow the whims and trends of the time, the skilled lyricist and member of the influential late-eighties hip-hop group Eric B. & Rakim chose to build steadily toward a singular style, wagering that staying the course would fix his place in the poetic firmament. Taking a que from Rakim’s energizing track Don’t Sweat the Technique, Newsom imbues his paintings with the spirit of the MC’s message: “You don’t have to speak, just seek / And peep the technique.”

Nature’s Course is on view through 6 p.m. today, Aug. 15. If you’ve yet to see it, get to the galleries — admission is always free.

Images:

Artist John Newsom and Director Jeremiah Matthew Davis give a tour of Nature's Course.

John Newsom's John Newsom: Nature's Course Catalogue (2022). Photo courtesy the artist.

Still shot of John Newsom from the short film Nature's Course. Produced by XEVOLVEZ on Apoplectic. Photo: XEVOLVEZ.

Collage wall in the Nature's Course: Learning Gallery. Photo: Alex Marks.

Installation view of John Newsom's State of the Union (2003-2004) and Labor of Love (2001). Photo: Alex Marks.

Raekwon's Fly international Luxurious Art (2015) album, original artwork by John Newsom and graphic layout by Eric Wiley.

Director Jeremiah Matthew Davis with John Newsom's Rogue Arena (2014). Photo courtesy the artist.

Return to New Light.